Photo: UNDP Montenegro

When the rain falls hard in the Western Balkans, it doesn’t respect borders. In the towns and villages along the Drin River Basin – shared by Albania, North Macedonia and Montenegro – floodwaters rush through farmland, swallow roads and leave families stranded.

For generations, people have endured these floods. But now, with climate change accelerating, the floods are arriving faster, lasting longer and hitting harder.

“This is exactly the view from my business when the floods hit,” said Robert Tonaj, pointing to a photo of his submerged garden. Robert owns a nursery in Shkodër in Albania, where he grows ornamental trees. “You can imagine my state of mind – seeing everything I’ve worked for underwater. It’s devastating, especially when your livelihood depends on the land and the plants you care for every day.”

Robert Tonaj, owner of Tonaj Nursery and Ornamental Trees in Dajç, Shkodër. Photo: UNDP Albania

Floodwaters submerge the garden of Robert Tonaj’s nursery. Photo: UNDP Albania

Robert’s story is far from unique. Across the Drin Basin, farmers, families and small businesses are grappling with rising flood risks that threaten not just property and productivity, but their sense of security and future.

In response, Albania, Montenegro and North Macedonia came together under a groundbreaking regional effort, supported by the Adaptation Fund (AF) and UNDP, to manage flood risk across borders. Building on foundational efforts supporting transboundary cooperation backed by the Global Environment Facility, the six-year project, now coming to a close, has invested not just in building barriers to floods, but also bridges between nations.

The Drin River Basin is one of the most flood-prone regions in the Western Balkans. Photo: Sead Sadiku, Director at the Administration Office of Drin-Buna Water Basin

Why the Drin River Basin matters

Spanning around 20,000 square kilometres, the Drin River Basin is one of the most complex and ecologically significant river systems in Europe. It stretches from the mountain lakes of North Macedonia to the coastal wetlands of Albania, passing through Kosovo* and Montenegro, extending into Greece, before emptying into the Adriatic Sea.

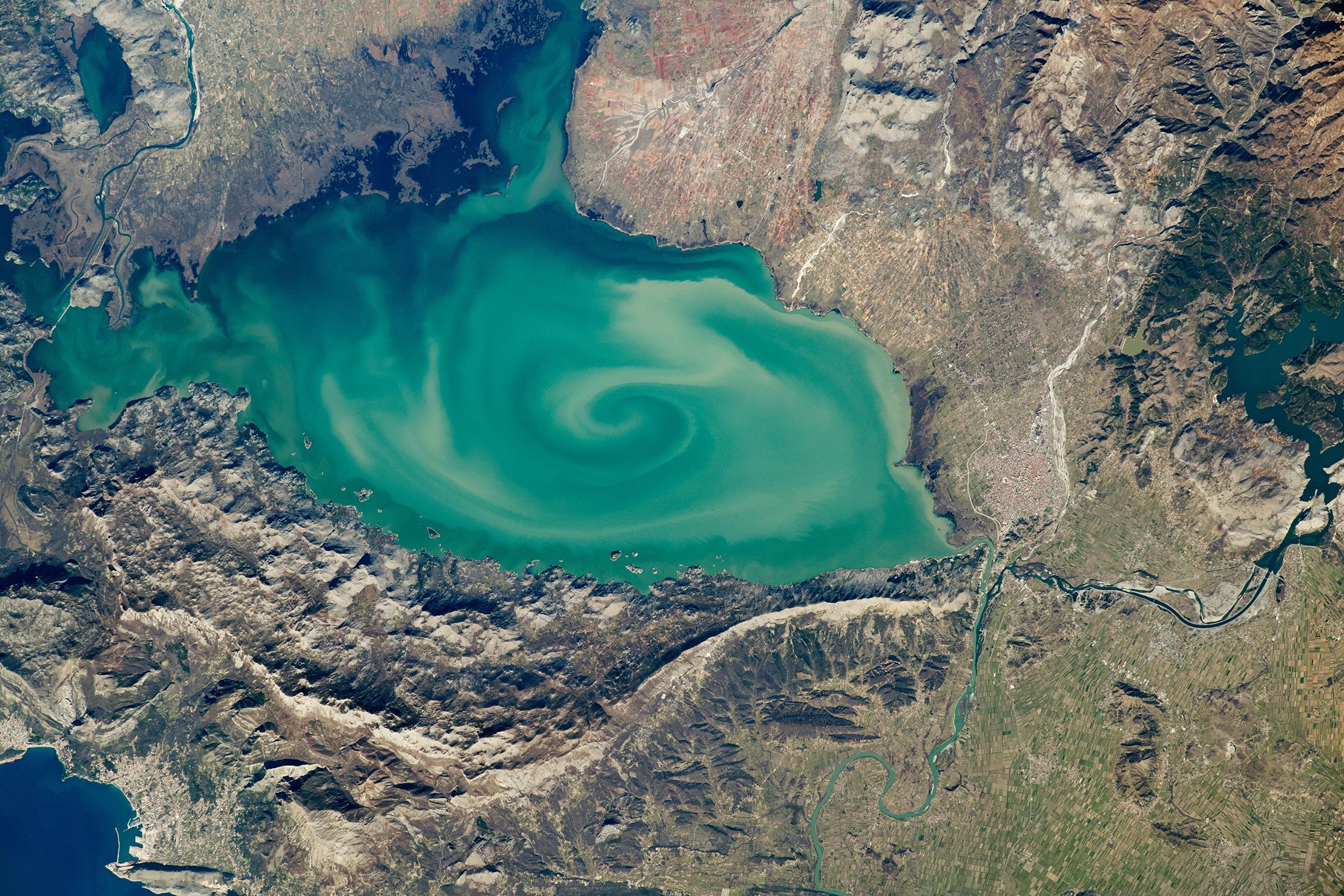

The basin is home to more than 1.6 million people and includes rare ecosystems like Lake Ohrid – Europe’s oldest lake, estimated to be more than two million years old – and Lake Shkodra, a critical bird habitat. It supports agriculture, tourism, hydropower and fisheries. But its communities also share a growing threat: climate-induced flooding.

Extreme rainfall events are becoming more common. Poor land management, deforestation and aging infrastructure only make things worse. Across the region, flash floods and river overflows disrupt lives, destroy livelihoods and damage economies already burdened by high unemployment and poverty, especially in rural and mountainous areas. Flooding in the Drin Basin causes approximately US$10 million in annual damages.

When it comes to climate change impacts such as flooding, it’s clear no country can face them alone.

Satellite view of Lake Skadar on the border of Montenegro and Albania, part of the Drin River Basin. Image: NASA

A shared solution

Launched in 2019, the $9.15 million AF-funded project brought Albania, Montenegro and North Macedonia together around one goal: to reduce the risk of climate-induced floods. The objective was to shift from fragmented, reactive responses to a unified, basin-wide, climate-resilient flood management strategy.

To achieve this, the project focused on three interconnected areas. First, strengthening climate and flood risk information, by expanding the hydromet monitoring network and laying the groundwork for more accurate forecasting and flood hazard mapping using state-of-the-art models.

Second, stronger policies and institutions, through support for the development of flood risk management strategies at national and basin levels, aligned with the European Union's (EU's) Floods Directive, while also promoting nature-based and gender-responsive approaches to adaptation.

Third, direct investment in community-level resilience, funding both structural measures – such as rehabilitated drainage systems and river embankments in the areas most vulnerable to flooding – and non-structural actions including early warning systems, community engagement and ecosystem restoration.

Together, these efforts aimed to reduce risk and build resilience for all 1.6 million people living in the Drin River Basin – particularly the 250,000 most directly exposed to flooding.

Albania: Reclaiming safety from the Buna River

For residents of northern Albania, the dangers of flooding are all too familiar. “My parents worked in the area for decades,” recalls Nora Kushti, Communications Specialist at UNDP Albania, originally from Shkodra. “I still remember being a kid, waiting to see if they’d make it home. When the [Buna] river overflowed, buses stopped running back to the city. Roads disappeared under water. My brothers and I waited by the phone. We checked the news. We didn’t know if they’d sleep at home or in a village nearby.” That was 40 years ago. Today, the floods – and the fear – only come more often.

With support from the project, Albania is rehabilitating the KK-5 drainage channel, a critical 5 km-long drainage system in the region. Once complete, the upgrade will improve land safety, protect homes and restore farmers’ confidence in their land. Meanwhile, local organizations are being engaged to implement nature-based solutions – like planting native vegetation and restoring natural water paths – to strengthen defences while preserving ecosystems. The river may still rise, but with the right investments, people won’t have to sink with it.

For residents of northern Albania, the dangers of flooding are all too familiar. Photo: Adaptation Fund

North Macedonia: Restoring rivers, protecting Lake Ohrid

In North Macedonia, the project focused on the Sateska River, which was diverted in 1961 from its natural course toward the Crni Drim River to flow directly into Lake Ohrid. The aim back then was to protect the Globocica reservoir – vital for electricity production – from sediment buildup. But the diversion had unintended consequences. Over the past 60 years, the river has carried large volumes of sediment into Lake Ohrid, damaging water quality, degrading habitats and threatening rare and endemic species. It has also increased flood risks for nearby communities, including Ohrid and Struga.

To date, the project has rehabilitated the riverbed, installed sediment traps and modernized the infrastructure. These efforts are easing flood risks and reducing ecological pressure on the lake.

“This project delivers a double ecological and socio-economic benefit,” said Ylber Mirta, Head of the Water Department in the Ministry of Environment and Physical Planning. “It protects communities and eases the ecological pressure of the Sateska River on Lake Ohrid, addressing UNESCO's concerns about its impact on the lake’s water quality and shoreline biodiversity.”

It is hoped that these works will pave the way for a lasting solution – returning the Sateska River to its original course and restoring balance to one of Europe’s most precious lakes.

Lake Ohrid is Europe’s oldest lake, estimated to be more than two million years old. Photo: UNDP

The diversion of the Sateska River to Lake Ohrid increased the risk of floods not just for the local communities along the river but also for the cities of Ohrid and Struga. Photo: Ariel Schindler/Adaptation Fund

When it comes to climate change impacts such as flooding, it’s clear no country can face them alone. Photo: Ariel Schindler/Adaptation Fund

Montenegro: Building defenses, building confidence

In Montenegro’s southern region of Ulcinj, flooding has repeatedly threatened homes and farmland, especially in the Bojana/Buna River basin. Hajrudin Osmanović, a farmer from the village of Bore, put it simply: “Every new day without adequate protection brings fear for our homes, families and everything we have been building for generations.”

With support from the project, Montenegro recently rehabilitated the Gropat–Štodra embankment, a long-eroded riverbank that once threatened thousands of hectares of agricultural land. Reinforced with environmentally sustainable stone, the embankment now safeguards nearly 2,000 residents and more than 7,000 hectares of productive farmland.

Montenegro’s government is now seeking additional funding to scale up this work and ensure long-term protection. Meanwhile, local emergency responders in Ulcinj have received new flood-response equipment, improving their ability to act quickly when storms hit.

Municipal representatives and Ministry of Interior officials participate in a Post-Disaster Needs Assessment training in Montenegro. Photo: UNDP Montenegro

Reconstruction of the Gropat–Štodra embankment on the Bojana/Buna River, shared between Montengero and Albania and the outlet of the Drin River Basin. Photo: UNDP Montenegro

A model for regional resilience

What makes this project transformative isn’t just the infrastructure – it’s the collaboration. For the first time, Albania, North Macedonia and Montenegro have a joint flood risk management strategy backed by shared data, aligned with EU standards and shaped by community voices. And it comes with a five-year action plan to reduce vulnerability across borders.

More than 33 hydrometeorological stations have been installed or upgraded across the three countries, improving monitoring of rainfall, river levels and other key indicators. Albania now uses a High-Performance Computing cluster, cutting flood model processing from days to hours and enabling early warnings one to three days in advance. GIS-based risk maps and vulnerability assessments support targeted interventions. The data is helping authorities better understand evolving risks, forecast extreme weather and issue earlier warnings – potentially saving lives and livelihoods.

Around 7,000 hectares of farmland are protected from flooding, restoring confidence among farmers who rely on the land to support their families and local economies. Municipalities across the basin have developed local flood action plans and adopted post-disaster assessment tools to ensure faster, more coordinated responses when disaster strikes.

As climate change accelerates, this cross-border collaboration offers a powerful model for other shared river basins around the world: one that shifts the focus from crisis response to long-term resilience, and from working alone to acting together.

The legacy of the project isn’t just stronger flood defences. It’s stronger institutions, smarter planning and communities better prepared for the challenges ahead.

During a recent visit, a delegation from the Adaptation Fund praised North Macedonia’s work as a model for integrated, sustainable flood risk management. Photo: Ariel Schindler/Adaptation Fund

*

With support from UNDP, the Global Environment Facility, the Global Water Partnership Mediterranean and the UN Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE), efforts to strengthen sustainable transboundary cooperation in the Drin River Basin continue. Learn more.

*References to Kosovo shall be understood to be in the context of Security Council Resolution 1244 (1999).