Photo: Michael Kibuku / UNDP Kenya

A farmer in northern Africa watches the sky for signs of rain, worrying that if it does not come, he will have to compete with pastoralists over grazing land. On a small island in the Pacific, families weigh the painful decision of leaving their ancestral land to escape the rising sea, aware that relocating to higher ground might strain relations with communities already living there. Near the dried marshlands and lakes of the Middle East, communities wonder how they can build a future in a place where they have to fight over water every morning.

Across the world, climate change is intensifying risks that deeply affect peace and security. In some places, extreme weather events can trigger competition over resources as access to food, water and livelihoods becomes increasingly contested in their aftermath. This, in turn, can undermine the rule of law, fuel unrest and lead to the displacement of marginalized groups. At the same time, in regions already burdened by conflict, the ability of communities and governments to adapt to climate change is eroded, creating a vicious cycle where climate stress and insecurity reinforce each other.

More than two billion people globally live in fragile and conflict-affected settings. For them, climate change is not only an environmental concern, but a harsh reality that decides whether families eat, children go to school or young people see a future. These challenges are not experienced equally. Women often shoulder the heaviest burdens, losing access to jobs or facing greater risks of violence when crises occur. Young people face disruptions to their education and employment and find it harder to build a stable future in rapidly changing environments. Indigenous Peoples, despite their deep knowledge of local landscapes, are often excluded from decision-making. When their perspectives and practices are ignored, communities lose access to generations of experience in managing land, water and ecosystems, knowledge that is vital for building resilience.

The link between climate, peace and security is not a simple chain of cause and effect. Climate change does not automatically lead to violence, but it multiplies security risks. A prolonged drought reduces crop yields, but whether this results in hunger, migration or conflict depends on whether fair systems exist to share water, settle disputes and support vulnerable families. Where governance is weak or exclusion is deep, climate shocks can become the sparks that ignite wider unrest.

That is why integrated solutions are essential. Climate action alone cannot secure peace, just as peacebuilding alone cannot shield communities from climate shocks. Together, however, they can foster more resilient communities and advance sustainable development.

In many fragile contexts, women fetch water, tend to farms and hold households together during crises. Photo: UNDP Timor-Leste / GCF

Timor-Leste is highly vulnerable to floods, droughts and landslides, which often destroy fragile infrastructure. Photo: Yuichi Ishida / UNDP Timor-Leste

People at the centre

The most effective responses to climate impacts begin with people themselves. Communities know where floods hit hardest, how grazing routes shift in drought or which families are most vulnerable when resources run low. When their voices guide decisions, solutions are more likely to endure. Women and youth must be central to these efforts. In many fragile contexts, women fetch water, tend farms and hold households together during crises, while young people can drive innovation and long-term resilience.

Timor-Leste is highly vulnerable to floods, droughts and landslides, which often destroy fragile infrastructure like roads and irrigation systems. As the government invested in climate-resilient infrastructure such as irrigation canals reinforced to withstand heavy rains, protective walls against flooding and roads designed for increasingly volatile weather, the approach mattered as much as the infrastructure itself.

Through an initiative supported by UNDP and the Green Climate Fund, traditional peace practices such as Tara Bandu (community agreements on resource use) and Nahe Biti Boot (negotiation ceremonies) were woven into the planning process. Women’s groups and youth organizations were actively included in consultations, ensuring that those most affected had a voice in shaping the solutions.

As a result, the infrastructure was not only physically resilient but socially embedded as well. Communities took ownership, ensuring systems were protected and disputes avoided. In one district alone, over 2,000 households gained year-round water access, reducing both climate vulnerability and the risk of conflict over scarce resources.

Iraq’s southern marshlands were drained during decades of conflict, leaving communities impoverished. Photo: UNDP Iraq

Women-led cooperatives make traditional handicrafts from locally available materials, tying livelihoods to ecosystem conservation. Photo: UNDP Iraq

Building trust through mediation

Even well-meaning solutions can backfire if they ignore local tensions. A borehole may reduce the burden of fetching water but can also spark disputes if one group feels excluded. Introducing new crops without consultation can fuel resentment. That is why conflict-sensitive design – anticipating risks, listening to grievances and ensuring fairness – is crucial.

Once famed for their biodiversity and cultural heritage, Iraq’s southern marshlands were drained during decades of conflict, leaving communities impoverished and ecosystems in ruins. Rising temperatures and declining river flows compounded the crisis.

The Government of Iraq, supported by UNDP and the Government of Sweden, undertook restoration efforts combining clean energy and economic opportunities. Solar-powered pumps brought drinking water back to isolated villages. Ecotourism projects created jobs linked to wetland preservation. Women-led cooperatives were supported to process and market traditional handicrafts, tying livelihoods to conservation.

But the real innovation lay in how conflicts were managed. When disputes arose over who benefited from restored areas or livelihood opportunities, community facilitators and mediators organized dialogues across tribes and villages. Grievances were aired, adjustments made and transparent rules established.

Within two years, more than 5,000 residents had improved access to water, while ecotourism brought new income to communities that once relied on unsustainable extraction of natural resources. Crucially, the process rebuilt trust in institutions and showed that environmental recovery could serve as a platform for peacebuilding.

As climate impacts accelerate, countries are becoming more water-stressed, often leading to a rise in social unrest and conflicts. Photo: Michael Kibuku / UNDP Kenya

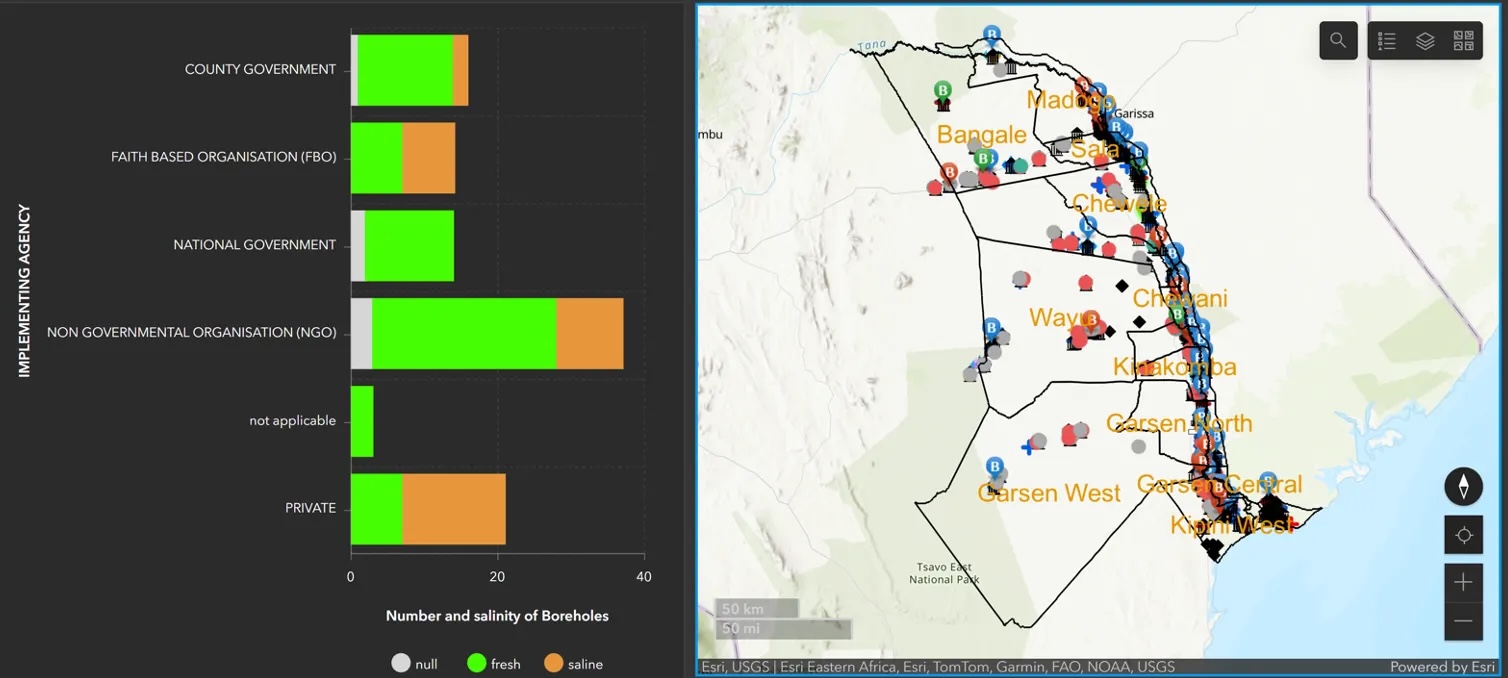

Combining satellite imagery with ground surveys carried out by local farmers and herders helped create a map of water sources in Kenya’s Tana River County. Photo: Michael Kibuku / UNDP Kenya

Blending technology and tradition

Technology can transform how communities prepare for and respond to climate risks, but only if it accessible and trusted. Satellite data, predictive modelling and early warning systems save lives, but their real power comes when combined with local knowledge and traditions.

For decades, pastoralists and farmers in Kenya’s Tana River County clashed during the dry season, when scarce water sources became flashpoints for violence. To change this, UNDP Accelerator Labs and local authorities worked with communities to map every borehole and riverbed using satellite imagery and ground surveys. The maps were shared openly in village meetings where herders and farmers negotiated grazing routes and water access in advance.

At the same time, solar-powered boreholes were installed in contested areas and strategic points along grazing routes, reducing pressure on rivers. Elders, women and youth were all part of the dialogue, ensuring rules were fair and widely accepted. Using solar energy also reduced dependence on diesel-powered generators that were polluting and costly to operate.

The results have been transformational. Incidents of violent clashes between farmers and pastoralists fell significantly in mapped areas, while over 30,000 people gained more reliable water access. What had once been a trigger for conflict became a foundation for cooperation, demonstrating how technology, when paired with traditional governance, can build peace as well as resilience.

In societies emerging from conflict, working together to heal damaged landscapes can rebuild trust and provide a common purpose. Photo: UNDP Colombia

In Colombia, forest restoration efforts brought together former combatants, Indigenous Peoples and farmers, restoring fractured relationships. Photo: Angely Castaño

Restoring nature, restoring peace

Restoring natural ecosystems is not just an environmental priority, it can also be a pathway to reconciliation. In societies emerging from conflict, working together to heal damaged landscapes can rebuild trust and provide common purpose.

In Colombia, following decades of armed conflict, deforestation surged in areas once controlled by illegal groups. Communities faced a stark choice: either return to harvesting illegal crops or find new livelihoods.

To resolve this, an initiative by UNDP and the Global Environment Facility brought together former combatants, Indigenous Peoples and farmers to restore forests and create sustainable economies. Reforestation initiatives provided paid work, sustainable agriculture reduced reliance on farming illegal crops, and ecotourism created new sources of income. By 2023, more than 7,000 hectares of forest had been restored, directly benefiting over 15,000 people.

Perhaps most importantly, former combatants and local farmers worked side by side. Protecting natural ecosystems became a shared mission, helping restore not just the land but also fractured relationships. Environmental stewardship became a bridge to reconciliation, showing how caring for nature can heal divisions left by war.

Integrated solutions for climate, peace and security

Experiences across conflict-affected and fragile regions show that climate action and peacebuilding are strongest when pursued together. The way ahead lies in scaling such integrated solutions – rooted in local realities, attentive to the climate-conflict dynamics and inclusive of marginalized voices.

Explore More Stories

Located on the borders between the West African countries of Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger is the landlocked region of Liptako-Gourma.