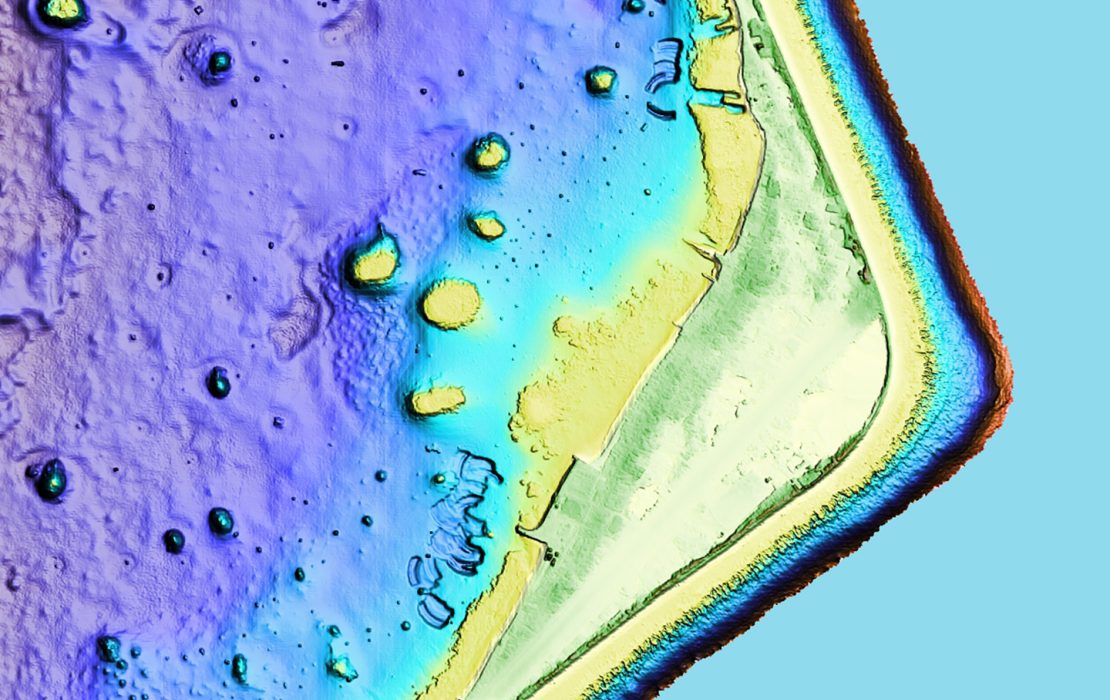

Nanumea atoll in Tuvalu, where new berm top barriers are being installed under the Tuvalu Coastal Adaptation Project to prevent wave overtopping, 2024. Photo: TCAP/UNDP

Throughout history, humans have turned to maps to unravel the mysteries of the world. The oldest known example, the Babylonian Map of the World, was etched in clay more than 2,500 years ago.

Over the centuries, of course, map-making has evolved and today, instead of dusty clay inscriptions, we have digital tablets alight with GPS constellations. More than 2,500 satellites now orbit the planet, providing invaluable data for understanding our world and supporting global communications and connectivity.

However, while our understanding of the world has dramatically expanded, it might surprise you to learn that we know very little about Earth’s coastal areas, including shallow waters less than 50 metres deep and low-lying coastal lands. We know less about these areas than the deep ocean floor of the planet, of which only 20 percent has been mapped to date according to recent estimates. Coastal areas are particularly difficult to map due to shallow depths unsuitable for survey boats and the presence of breaking waves and reefs.

This is a hugely concerning gap when it comes to understanding and preparing for the impacts of climate change on coastal areas, including sea level rise and storm waves. Here’s why and how we must urgently fill this gap, particularly when it comes to the world’s low-lying Small Island Developing States (SIDS).

Understanding the ocean and what’s underneath it for effective coastal adaptation

In recent years, light detection and ranging (LiDAR) technology has emerged as an extraordinarily exciting advance that allows the accurate collection of data on land surface height and sea floor depth – in the form of 3D mapping – from the air. Taken together with satellite systems which measure sea level rise globally with sub-millimetre accuracy, we have the data to better understand the problem and design appropriate adaptation solutions.

Yet, in many developing countries, especially in SIDS, such data continues to be lacking. What this means is that one of the most important questions for SIDS worldwide – how high are the islands and how soon will waves and sea level rise overwhelm them – remains very poorly answered.

Coastal communities and infrastructure face relentless oceanic forces – incessant waves, daily tides, yearly bulges from solar gravitational forces and sporadic cyclone impacts, all against a backdrop of rising sea levels. In the Caribbean, 22 million people live below 6-metre elevation and nearly 90 percent of Pacific Islanders (except Papua New Guinea) live within 5 kilometres of the coast. More than 50 percent of infrastructure is located within 500 metres of the coast in most Pacific islands. Tropical cyclones in the past have caused significant damage to people and assets in coastal communities. Between 1995-2022, 185 tropical cyclones in the Caribbean and 74 in Oceania and the Pacific have caused US$47 billion in damages.

Accurate sea-level data, combined with an understanding of the depth and shape of coastal terrain, enables more precise modelling of marine hazards. This is absolutely crucial for effective coastal protection and adaptation, especially in low-lying SIDS.

In a worst-case scenario, in which levels of greenhouse gas emissions remain high, global mean sea-level is projected to rise about 88 centimetres by 2100. Therefore, improving the ability of island states to put in place robust coastal adaptation measures is urgent – in some cases, existential.

Survey plane equipped with LiDAR mapping technology readies for take off in Tuvalu, 2019. Photo: Arthur Webb/UNDP

Sapolu Tetoa from Tuvalu's Lands and Survey Department (seated) and Tomasi Sovea, Senior Officer at SPC (standing) analyze LiDAR data via a platform developed under the Tuvalu Coastal Adaptation Project. Photo: Merana Kitione

Why does the data gap persist and how can we address it?

While the international community has been increasingly vocal about supporting SIDS in the fight against climate change, the critical question remains: why do we still face such a fundamental gap in data that is essential for the long-term resilience of island states?

One of the reasons data is sorely lacking in SIDS is the cost. Collecting data in the coastal zone using LiDAR is an investment beyond what many SIDS governments can afford. Faced with the pressing need to tackle the climate crisis alongside other development challenges, SIDS governments frequently prioritize immediate needs such as disaster risk reduction and water and food security. Consequently, investments in data collection – although essential for enhancing the effectiveness of these urgent measures – are pushed down the priority list.

Another challenge lies in how international support is provided to countries. International climate finance, especially from public sources, is predominantly funneled into specific projects, which are often scarce and infrequent.

One solution to this challenge is to pool resources from interested donors specifically for the purpose of gathering this crucial information. Unlike socioeconomic data, which require frequent updates, data collected from bathymetric and topographic surveys do not become obsolete. Therefore, a one-time investment can yield lasting benefits by better informing future coastal adaptation measures, provided the data is managed effectively by an institution that has specialized skills and experience in managing such data.

A model from Tuvalu

The small Pacific Island nation of Tuvalu offers a promising model for addressing these issues. With financing from the Green Climate Fund (GCF) and technical support from UNDP, Tuvalu has successfully mapped all nine of its atoll systems, including the islands and surrounding reefs and lagoons — covering approximately 500 square kilometres in total — utilizing airborne LiDAR.

In just over 37 hours of flight time, Tuvalu acquired extremely high-resolution bathymetric and topographic data, which is being utilized in infrastructure planning and risk modeling. This invaluable baseline will assist the government as it navigates the complexities of the climate crisis.

Crucially, the data is managed by the Pacific Community (SPC), a regional organization that serves 27 Pacific member countries and territories. SPC is equipped to archive and analyze the data whenever Tuvalu requires it.

1971 black and white aerial photograph of Fogafale, Tuvalu.

2020 3D-LIDAR model of Fogafale, Tuvalu, with colour overlay. Photo: TCAP/UNDP

The "Tuvalu model" can be replicated. However, it should not rely solely on each country’s ability to design projects and access climate finance as Tuvalu has done. A global investment could cover all SIDS, providing them with essential maps detailing the coastal zone. The levels of funding are not inconceivable if the international community is genuinely committed to assisting SIDS in building long-term resilience. For example, the Tuvalu national dataset cost around $1 million but has been used to successfully attract adaptation funding many times this amount.

Like the ancient Babylonian maps, bathymetric and topographic maps hold a wealth of information, equipping SIDS as they navigate an uncertain and likely challenging future. This a critical missing piece in the puzzle of long-term resilience for these highly vulnerable nations.

***

UNDP currently supports more than 11 SIDS worldwide to implement climate change adaptation projects, including coastal adaptation projects in Tuvalu, Cuba, Guinea-Bissau and a newly approved project in Tonga, as well as support to countries such as Papua New Guinea and Haiti to develop National Adaptation Plans for the future.

Under the global strategy, “SIDS Rising 2.0”, UNDP is rolling out support to drive forward blue and green economies focused on nature-based solutions and with digital transformation as one of its key pillars.