Photo: WHO Timor-Leste

As global temperatures rise, the risks to human health are escalating. Climate change is expected to cause around 250,000 additional deaths each year between 2030 and 2050, due to the rising incidence of malnutrition, malaria, diarrhoea and heat-related illnesses.

Health systems worldwide are faced with these threats, meaning they need to find ways to adapt to increasing climate change impacts. But nowhere are the challenges greater than in the world’s Least Developed Countries (LDCs), where limited resources and fragile infrastructure leave communities especially vulnerable.

In Asian LDCs, significant health gains have been made over the past 25 years, seen in reduced infant mortality, increased life expectancy and progress in controlling many communicable diseases. But climate change threatens to reverse that progress, with rising temperatures, more frequent floods and droughts, and changing patterns of disease putting growing pressure on already overstretched health systems.

Projections based on current policies suggest global temperatures could rise by as much as 3.1°C above pre-industrial levels by the end of the century. This would dramatically increase the risk of deadly heatwaves, disease outbreaks, food and water insecurity, and the collapse of already strained health systems.

LDCs face a dual burden: they are often highly exposed to climate hazards and have limited capacity to respond. Early warning systems often don’t reach rural clinics. Climate data is rarely integrated into disease surveillance. Health facilities struggle to cope with extreme weather, and most public health workers receive little to no training on the links between climate and disease.

But change is underway in some of Asia’s most climate-vulnerable countries, helping frontline services to better anticipate, prepare for and respond to the health impacts of a warming world.

Recognizing the urgent need to strengthen climate resilience in public health, a major regional project to build the climate resilience of health systems in Asian LDCs was launched in 2019. Funded by the Global Environment Facility's Least Developed Countries Fund and implemented by UNDP and the World Health Organization (WHO), the five-year project aimed to boost the adaptive capacity of health systems in six countries: Bangladesh, Cambodia, Lao PDR, Myanmar, Nepal and Timor-Leste. While activities in Myanmar were suspended in 2021 due to political instability, the project continued in the other five countries, adapting to COVID-19 constraints along the way.

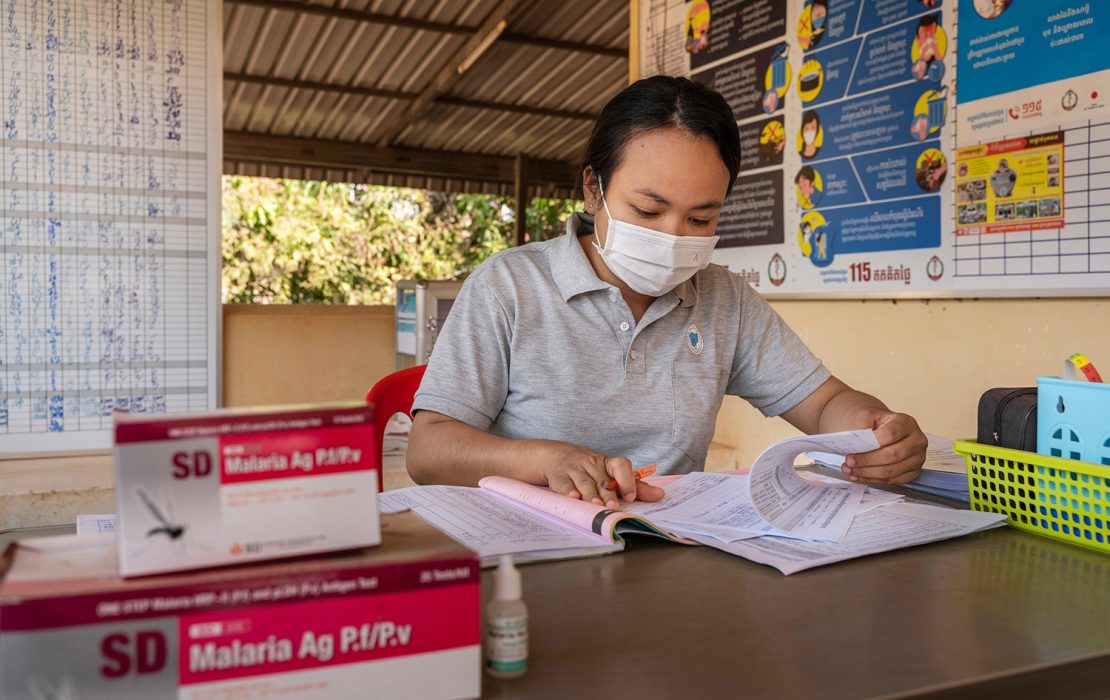

Cambodia’s Nationally Determined Contribution recognizes the impact of climate change on health, especially affecting children and the elderly, setting out five priority actions for adaptation. Photo: WHO Cambodia/Aforative Media

Cambodia has developed standard operating procedures for dengue and surveillance and rapid diagnostic testing, using them as a basis for training 120 doctors, nurses and other health professionals from high-risk provinces. Photo: WHO Cambodia

Planning for a healthier, climate-resilient future

One of the regional project’s most tangible legacies is a suite of Health National Adaptation Plans (HNAPs). HNAPs serve as national frameworks to address the health risks of climate change, by setting priorities for action and ensuring that climate adaptation planning in the health sector is systematic and evidence-based. By integrating health into broader climate policy, HNAPs help countries build more coordinated, resilient and inclusive responses to growing climate risks.

With support from WHO, all five countries completed and endorsed these crucial strategic blueprints. These plans now underpin national health adaptation measures and have helped integrate health into wider climate policymaking. Taking it a step further, Nepal, Bangladesh and Timor-Leste made significant progress in integrating their HNAP with their overall National Adaptation Plans (NAPs), providing a model of best practice for other countries.

At the same time, the five countries have developed or adopted more than 40 new policies, guidelines and practical tools, helping them prepare their health systems for climate change impacts. These cover a wide range of areas, from climate-informed early warning systems for disease outbreaks, to safer water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) in health facilities in climate vulnerable areas, to better healthcare waste management. Many of these policies, guidelines and tools were based on global best practices but tailored to fit local needs. For example, Cambodia developed standard operating procedures for dengue surveillance and rapid diagnostic testing based on international WHO guidance. In Bangladesh, the Ministry of Health published new national WASH standards for healthcare facilities. Timor-Leste developed a healthcare waste management policy as well as national guidelines for water quality testing.

Bangladesh has made significant progress in integrating its HNAP with its NAP, ensuring that health is systematically addressed in national climate policy and better positioned to access adaptation finance and coordinate across sectors. Photo: AB Rashid / UNDP Bangladesh

Bangladesh’s Nationally Determined Contribution acknowledges the health sector's vulnerability to climate change impacts and outlines steps to address climate change in a way that also improves the health and well-being of people. Photo: AB Rashid / UNDP Bangladesh

Workshops organized under the project helped train national and local health officials to apply these tools, and governments are taking real ownership. In Lao PDR, the Ministry of Health recognizes the ‘Safe, Clean, Green, Climate-Resilient Hospital Toolkit’ developed under the project as a national resource – showing strong commitment to using and sustaining these efforts.

The project has also invested in people. Thousands of health professionals – from rural nurses to central ministry officials – received training on climate and health issues. Bangladesh developed teaching materials on climate change and health for medical educators to support the training of a climate-resilient health workforce. As a result, over 500 staff across 100 health facilities now have the knowledge and skills needed to respond to climate risks. Lao PDR, meanwhile, incorporated a nine-module climate and health curriculum into academic programmes. Cambodia rolled out community training and behaviour change programmes for dengue and diarrhoeal diseases, as well as WASH awareness in villages across Rantanakiri, a province which has some of the worst health indicators in the country. In Nepal, a national training manual on climate and health, developed under the project, is now regularly used by the National Health Training Centre and provincial governments to train health professionals across the country.

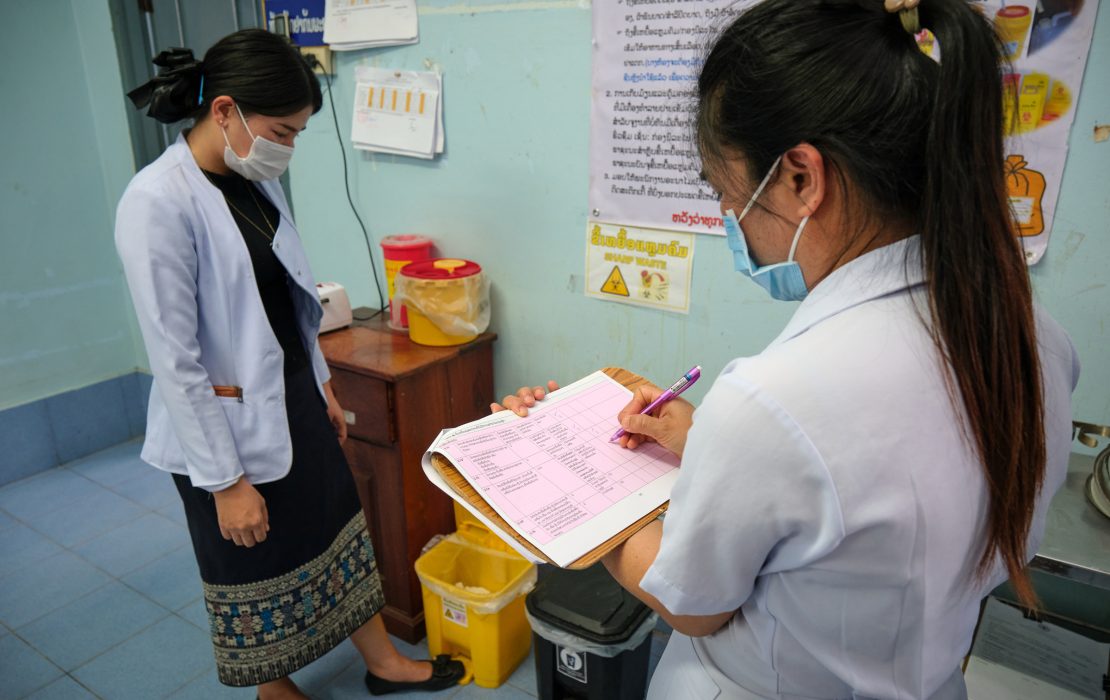

Healthcare workers in Lao PDR review climate-health safety procedures, part of national efforts to improve waste management and build resilient health systems in the face of climate change. Photo: WHO Lao PDR

Lao PDR has developed a comprehensive nine-module climate and health training programme and integrated it into academic curricula to build long-term institutional capacity. Photo: WHO Lao PDR

Across all five countries, health surveillance systems also took a leap forward. Each country piloted integrated early warning systems for climate-sensitive diseases like dengue, cholera and diarrhoeal illnesses. In Lao PDR, the Ministry of Health launched a pilot Climate Integrated Early Warning and Response System (CI-EWARS). This innovative system combines weather data—such as rainfall, temperature and humidity—with health monitoring to predict outbreaks of climate-sensitive diseases. In Nepal, a partnership between the Department of Health Services and the Department of Hydrology and Meteorology was established to enable data sharing. This allowed the piloting of a climate-sensitive disease surveillance system that integrates health and weather data to forecast potential outbreaks.

On the ground, pilot initiatives brought theory into practice, providing proof of concept for future investments. For example, in a bid to strengthen the surveillance of climate-sensitive diseases, Bangladesh has embarked on a pilot using the Early Warning, Alert and Response System (EWARS) tool developed by WHO. The pilot was conducted across 10 sentinel hospital sites (selected hospitals that track key health trends or diseases) focusing on diseases such as dengue, cholera, diarrhoea and rotavirus.

Timor-Leste’s Nationally Determined Contribution cites enhancing the capacity of the health sector as a key priority in adapting to climate change. Photo: WHO Timor-Leste

Timor-Leste finalized and endorsed its HNAP in 2022. The country has developed a national policy and strategy on Climate Resilient and Environmentally Sustainable Healthcare Facilities. Photo: WHO Timor-Leste

In Nepal, through another pilot initiative, 219 healthcare and administrative staff from three healthcare facilities strengthened their skills related to climate resilience and environmental sustainability. This initiative also introduced proper healthcare waste management systems, including the use of non-burn technologies, which contributed to safer practices and reduced carbon emissions.

Perhaps most importantly, the project helped embed climate awareness into health governance. Technical working groups were established within health ministries to lead the implementation of HNAPs. Health officials participated in international climate forums, including the UNFCCC Conference of the Parties (COP) meetings and WHO’s Alliance for Transformative Action on Climate and Health (ATACH), raising the profile of health issues within global climate discussions and negotiations.

Nepal has conducted a baseline assessment of greenhouse gas emissions from the health sector, which accounts for 4.1 percent of the country’s total emissions. Photo: WHO Nepal

Nepal has conducted a vulnerability and adaptation assessment for the health sector, updated its Health National Adaptation Plan and integrated health targets into its Nationally Determined Contribution. Photo: WHO Nepal

The road ahead

The project has shown what is possible when climate and health priorities are tackled together, not in silos. But it also revealed the scale of the challenge ahead. Funding for implementation remains patchy. Long-term coordination between ministries must be strengthened. And while pilots have shown promise, scaling them up will require continued political and financial support.

Still, the groundwork has been laid. The participating countries now have stronger institutions, clearer plans and a growing cadre of trained professionals ready to lead the next phase of action. As the climate crisis deepens, their experience offers a model for how health systems everywhere can rise to meet it – with resilience, innovation and local leadership.

*

The project "Building Resilience of Health Systems in Asian LDCs to Climate Change" was funded by the Global Environment Facility's Least Developed Countries Fund (LDCF) and implemented by UNDP and the World Health Organization (WHO). A similar regional project, implemented by WHO and UNDP, with funding from the Least Developed Countries Fund, in Pacific LDCs is underway.