Summary

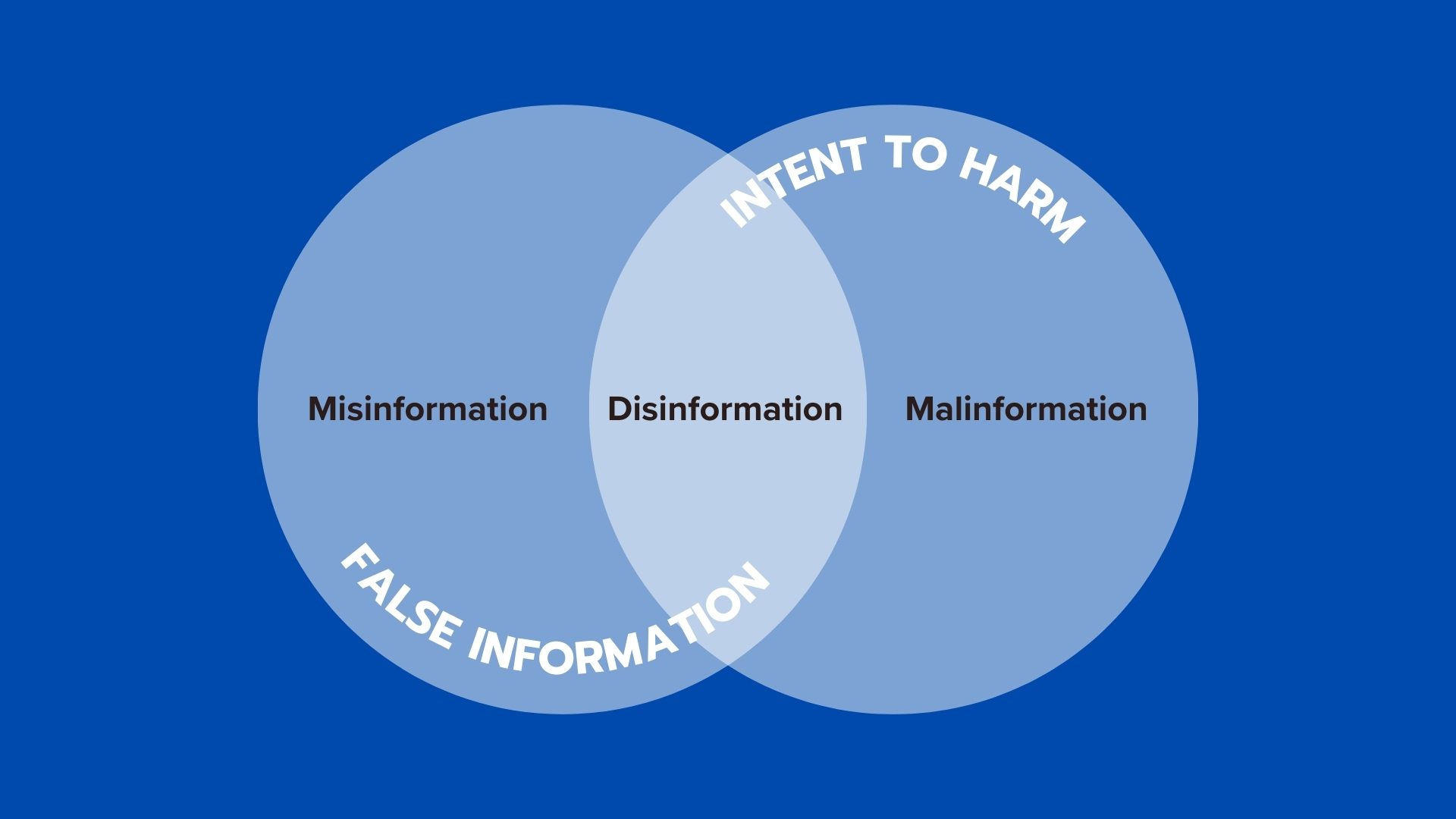

- Climate misinformation refers to false or inaccurate information about climate change and climate action that is generally spread without malicious intent.

- Climate disinformation is deliberately false and fabricated to deceive people about climate change and climate action for political, financial or ideological reasons.

- Climate denial, climate delay, greenwashing and conspiracy narratives are some forms of climate misinformation and disinformation.

- Climate misinformation and disinformation spread due to the formation of echo chambers, algorithmic bias and abuse by malicious actors.

- In regions already stressed by environmental pressures, climate misinformation and disinformation can exacerbate existing tensions and undermine local peacebuilding efforts.

- The fight against climate misinformation and disinformation is a global effort, involving governments, academic organizations, think tanks, media organizations, civil society and citizens.

What is the difference between climate misinformation and climate disinformation?

Climate misinformation refers to false or inaccurate information about climate change and climate action that is generally spread without malicious intent. It usually arises from misunderstandings, misinterpretations of data or simply outdated knowledge. For example, some people might misinterpret short-term weather patterns, like an extended winter season, as evidence against global warming. Despite the absence of intent to deceive, misinformation still contributes to confusion and scepticism about climate science, making it harder for people to access accurate information.

Climate disinformation, on the other hand, is deliberately false and fabricated to deceive people about climate change and climate action for political, financial or ideological reasons. It is spread by individuals or organizations with vested interests in denying or downplaying the reality of climate change and its impacts. For instance, fossil fuel companies have been known to fund campaigns that cast doubt on climate science to protect their profits.

Disinformation tactics can include cherry-picking data, promoting pseudoscience, or amplifying conspiracy theories. Unlike misinformation, which can often be corrected through education and better communication, disinformation is more difficult to address and requires targeted efforts to expose and counter the deliberate falsehoods being spread.

Both climate misinformation and disinformation undermine public trust in climate science, delay policy responses and polarize public discourse. According to the Global Risk Report 2024, misinformation and disinformation, together with the impacts of the climate and nature crises, are the biggest short-term and long-term risks to human society.

Climate misinformation is generally spread without malicious intent. Climate disinformation, on the other hand, is deliberately false and purposefully harmful for political, financial or ideological reasons.

What are the different types of climate misinformation and disinformation?

Climate misinformation and disinformation come in various forms, each serving different purposes but ultimately hindering climate action. While some outright deny climate change, others seek to delay solutions, mislead the public or promote conspiracy theories that undermine trust in science and institutions.

- Climate denial: Despite the overwhelming scientific consensus that human activities like burning fossil fuels are the primary driver of climate change, some people deny that climate change is real, downplay the severity of its impacts or promote the idea that it is solely a natural phenomenon. Although outright climate denial has lost credibility in mainstream discourse, it still thrives in certain political and online spaces, often resurfacing in the form of misleading arguments that exaggerate natural climate variability or misrepresent climate data. A subtler form, known as soft climate denial, is becoming increasingly prevalent in recent years. Here, individuals or groups acknowledge the impacts of climate change but tend to highlight other urgent issues as a justification for delaying or opposing responses. This approach, often framed as pragmatic, effectively serves as a guise for undermining climate action.

- Climate delay: Climate delay strategies acknowledge the existence of climate change but aim to obstruct or hinder action. They dispute the feasibility, necessity or fairness of climate policies by claiming measures are too costly or emphasizing uncertainties and unintended consequences. For example, messaging from the fossil fuel industry aims to create panic about potential job losses and economic harm from transitioning to renewable energy sources. Because climate delay messages often seem more reasonable than outright denial, they are particularly effective at shaping public opinion.

- Greenwashing: Greenwashing is a form of climate misinformation in which companies or institutions exaggerate or falsely claim environmental benefits to maintain their market position without making real changes. This is usually done by using imagery and language associated with sustainability such as lush forests, wind turbines or eco-friendly branding. Such tactics delay stronger policies and regulations by creating an illusion of progress.

- Climate conspiracy narratives: Conspiracy theories about climate change attempt to delegitimize climate science, policies and activists by suggesting they are part of a hidden agenda. These narratives try to advance false claims such as climate change being a hoax designed to increase government control or renewable energy policies being part of a larger effort to manipulate economies or suppress individual freedoms.

Who spreads climate disinformation?

Considering the scale and urgency of the climate crisis, it may seem counterintuitive that individuals or organizations would deliberately create and share false or misleading information about it. However, research points to two primary motivations behind the spread of climate disinformation:

- Protecting fossil fuel interests and maintaining a business-as-usual scenario: Many actors, particularly within the fossil fuel industry and related sectors, have a vested interest in delaying climate action. By spreading doubt about climate science or the effectiveness of renewable energy solutions, they seek to extend the viability of fossil fuels and maintain economic gains.

- Gaining revenue, influence or support by exploiting the attention economy: The digital landscape rewards content that sparks strong emotional reactions like outrage or controversy. Questioning mainstream science or promoting conspiracy theories can generate more engagement on social media, translating into ad revenue, online influence or political support.

Moreover, in regions already stressed by environmental pressures such as resource scarcity and extreme weather events, climate misinformation and disinformation can exacerbate existing tensions. False information and narratives, for example around climate-induced migration and displacement, are often exploited by political actors or extremist groups to blame specific communities for climate-related hardships, creating an environment of fear and mistrust which can lead to violence and conflicts. This not only undermines local peacebuilding efforts but also links climate challenges with broader issues of security, destabilizing communities and economies while hindering integrated responses to both environmental and security threats.

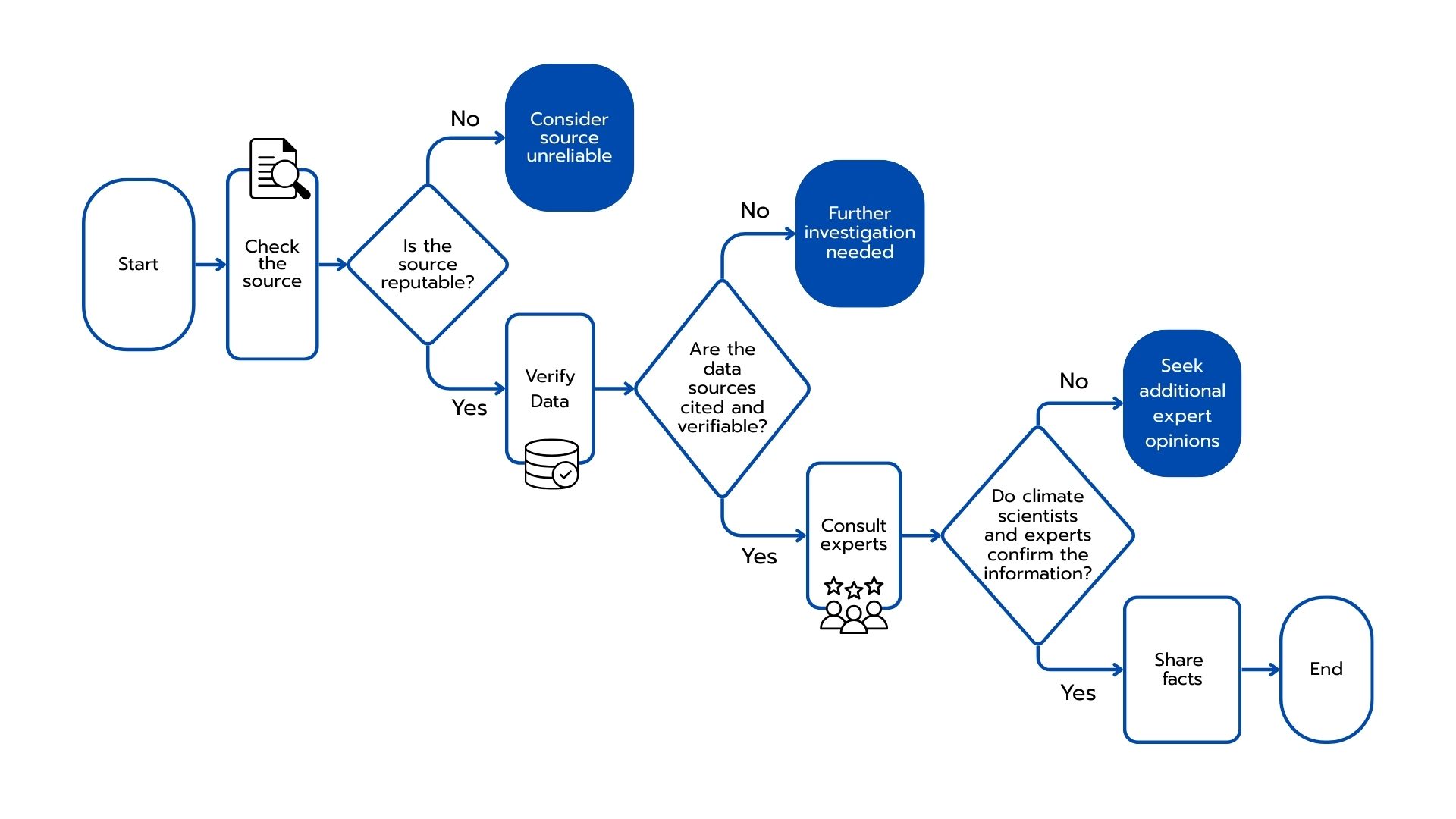

Individuals can learn how to verify the accuracy of a piece of information through a series of steps including verifying the source, verifying the data and consulting with experts.

How do climate misinformation and disinformation spread?

The spread of climate misinformation and disinformation, both online and offline, is linked to social processes that shape how people interact and consume information. These dynamics contribute to the reinforcement of false narratives, making it harder to correct misinformation and disinformation once it takes hold.

As social beings, humans have the tendency to form social connections with others who share similar beliefs, interests or backgrounds. Social media platforms reinforce this behaviour by recommending new connections based on existing networks and interests. Combined with the natural inclination to trust information from familiar sources, this leads to the formation of echo chambers – closed communities where the same ideas, whether true or false, are continuously reinforced without being questioned. Over time, these echo chambers can deepen divisions on topics such as climate change.

Furthermore, many social media algorithms are designed to maximize engagement. As such, they often promote content based on a user’s past interactions, rather than its credibility or accuracy. This creates algorithmic bias, where users are more likely to see content that aligns with their existing beliefs, rather than diverse or fact-based perspectives. The effect is then amplified by confirmation bias – the psychological tendency for people to seek out and accept information that supports their pre-existing views while ignoring or dismissing contradictory evidence. As a result, misleading or sensationalized climate content can spread rapidly, especially if it resonates with a particular audience’s worldview.

Beyond organic social behaviours, false information is also actively spread by malicious actors, including bots, trolls and coordinated disinformation campaigns. These actors deliberately create and amplify misleading narratives to shape public perception, undermine trust in scientific institutions or serve certain political and economic interests.

A recent example is a rise in online abuse against climate scientists, where coordinated campaigns on social media platforms target researchers with harassment and false accusations to discredit their work. These attacks often exploit existing echo chambers, amplifying divisive narratives that portray climate science as a hoax or conspiracy. By leveraging algorithmic biases and the viral nature of sensational content, these campaigns sow doubt and erode public trust in evidence-based solutions. This not only undermines efforts to address climate change but also discourages scientists from engaging with the public, further polarizing the discourse and hindering collective action.

How can we tackle climate misinformation and disinformation?

The fight against climate misinformation and disinformation is a global effort, involving a diverse range of actors including governments, academic organizations, think tanks, media organizations, civil society and collaborative partnerships between these entities. Given the high complexity of the issue, it requires multifaceted responses, and these actors play key roles in research, policy advocacy, education and public outreach. Through specialized initiatives and campaigns, they work to address the challenges posed by misinformation, which often undermines public understanding of climate science, fuels scepticism about climate change and hinders policy action.

Recognizing that misinformation, disinformation and hate speech are fuelling conflict, threatening democracy and human rights, the United Nations launched the United Nations Global Principles for Information Integrity, a set of recommendations designed to foster healthier and safer information spaces that champion human rights, peaceful societies and a sustainable future. Moreover, in November 2024, the Brazilian government, the United Nations and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) launched the Global Initiative for Information Integrity on Climate Change, joining forces to strengthen research and measures to address disinformation campaigns that are delaying and derailing climate action.

However, a large majority of efforts to combat climate misinformation and disinformation are still primarily based in the Global North, which often leads to a skewed focus on issues, narratives and perspectives that are more relevant to them. In this context, it is essential to build the capacities of stakeholders and institutions in the Global South to tackle climate misinformation and disinformation. By empowering local organizations, media and communities with the necessary skills, knowledge and resources, we can ensure that climate communication and responses to disinformation are more culturally appropriate and contextually relevant.

At the individual level, anyone can learn how to prevent climate misinformation and disinformation through a series of steps:

- Verify the source: Evaluate the credibility of the source. Is the claim from a peer-reviewed study, a reputable news outlet or a blog with no scientific backing? For scientific data, academic databases and peer-reviewed sources can be used to verify its authenticity.

- Verify the information: Check if the information is available from multiple sources and use fact-checkers to verify claims.

- Consult experts: Try to connect with scientists and subject matter experts that can corroborate the information. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is widely recognized as the most credible source of information related to the science of climate change.

- Communicate the truth: To counter climate misinformation and disinformation, evidence-based messages using simple language and relatable examples work best. Engage trusted voices and support claims with credible sources, encouraging respectful dialogue. Repetition of accurate information helps build long-term public understanding and resilience.

In Somalia, UNDP trains journalists to enhance their understanding of climate change issues. Photo: UNDP Somalia

In Montenegro, UNDP supports young activists to counter online hate speech. Photo: Duško Miljanić

How does UNDP support efforts to address climate misinformation and climate disinformation?

UNDP works to address climate misinformation and disinformation through a multi‐pronged approach that combines digital innovation, capacity building and partnerships. This includes developing programmes and platforms that leverage collective intelligence, combining automated tools and crowdsourcing to identify and counter false narratives.

Digital tools such as iVerify and eMonitor+ combine AI with human fact-checking to identify, flag and counter false and misleading narratives including those for climate-related issues. Such platforms, developed as part of UNDP’s broader digital strategy to leverage Digital Public Infrastructure, harness interoperable systems for data exchange and digital identity, supporting transparency and accountability in climate action by helping to counter information that undermines scientific consensus on climate change.

UNDP also supports initiatives aimed at developing media literacy and factchecking skills among journalists, media students and young civic actors. In Somalia, UNDP trains journalists to enhance their understanding of climate change issues, their interlinkages and nuances. In Lebanon, UNDP helps equip young people with the tools to identify and debunk fake news and hate speech, including false narratives on climate change. Such efforts help reduce the polarization and confusion often fuelled by false information, particularly in regions vulnerable to climate misinformation and disinformation campaigns.

Furthermore, through initiatives like Information Integrity, UNDP is working with development organizations, governments, the private sector and civil society on campaigns to ensure information integrity on issues directly and indirectly affecting climate action.